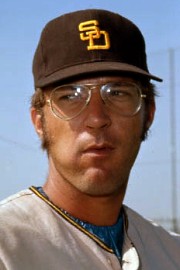

The Padres’ Mark Schaeffer: On the Outside Looking In

Credit: Topps

Santa Monica has produced some outstanding ballplayers. The late Dan Quisenberry, the relief pitcher for the Kansas City Royals. The great Dwight “Dewey” Evans, the strong-armed right fielder for the Boston Red Sox. Tim Leary, the starting pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Current New York Mets pitcher Robert Gsellman. And Pete O’Brien, the first baseman for the Texas Ranger and Seattle Mariners.

All of them, and their loved ones, either are receiving or can expect MLB pensions for life.

Mark Schaeffer does not.

In his only year in the big leagues, Schaeffer pitched for the 1972 San Diego Padres and appeared in 41 games, all in relief. In 41 innings, he won two games and saved one other.

Hardly Hall of Fame credentials. I mean you wouldn’t trade a Dave Winfield or a Randy Jones card for Schaeffer’s—well, maybe you would – but he made it to “The Show” and all I do is write about baseball.

Nowadays, Schaeffer’s numbers would guarantee him a minimum pensions of $34,000 per year. But he doesn’t receive anywhere near that amount.

As most readers of the East Village Times know from my past posts, Schaeffer don’t receive traditional pensions because the rules for receiving MLB pensions changed in 1980. Schaeffer and the other men do not get pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit. That was what ballplayers who played between 1947 – 1979 needed to be eligible for the pension plan.

Instead, they all receive non-qualified retirement payments based on a complicated formula that had to have been calculated by an actuary.

In brief, for every quarter of service a man has accrued, which is defined as 43 game days of service, he gets $625. And that payment is before taxes are taken out.

By contrast, the maximum allowable pension a retired MLB player who is vested can make is $220,000. Even the minimum pension for a post-1980 player with only 43 game days of service is a reported $34,000.

What’s more, the payment cannot be passed on to a surviving spouse or designated beneficiary. So none of Schaeffer’s loved ones will receive their respective payments when they die.

These men are also not eligible to buy into the league’s umbrella health insurance coverage plan.

Schaeffer is being penalized for playing the game he loved at the wrong time.

Though Forbes recently reported that the current players’ welfare and benefits fund is valued at more than $2.7 billion, the MLBPA has been loathe to divvy up more of the collective pie. Many of the impacted retirees are filing for bankruptcies at advanced ages, having their homes foreclosed on and are so poor and sickly they cannot afford adequate health insurance coverage.

Tony Clark, the first former player ever to run the players’ association, refuses to go to bat for the non-vested men like Schaeffer, in spite of the fact that, when he received the coveted Jackie Robinson Lifetime Achievement Award from the Negro Leagues Museum in Kansas City, in June 2016, the former Padre referenced a quote from the late Muhammad Ali.

“Success is what you achieve,” said Clark. “Your significance is what you leave.”

If Clark actually does something about this situation, he really would be leaving Schaefer and all the other men something of great significance. And that would be a nice achievement on his part.

Freelance magazine writer.

Advocate for MLB players rights

Interesting take. I hope something is done to divide up the pie more fairly.